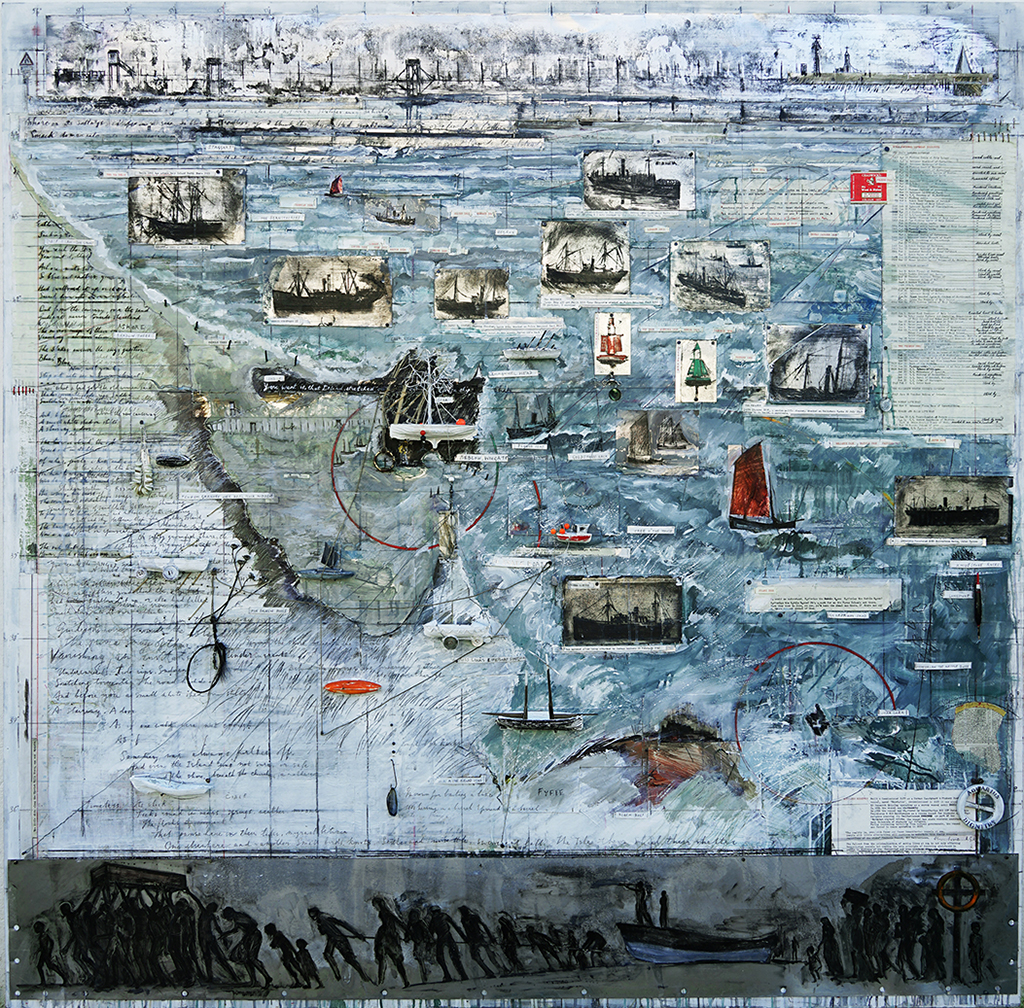

Shifting Sands

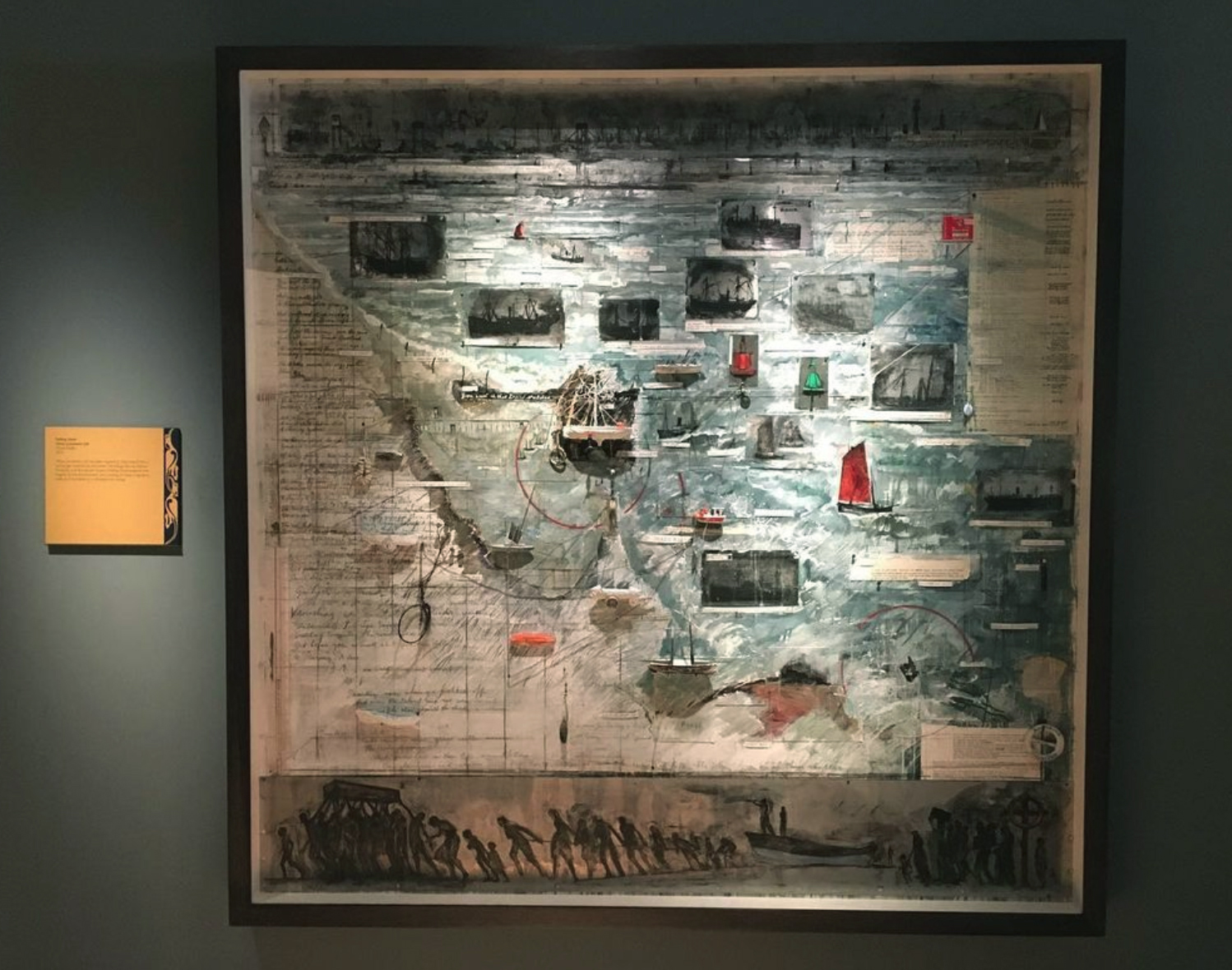

In 2022 Olivia Lomenech Gill was commissioned by English Heritage to produce a large painting to be hung in the newly-renovated museum at Lindisfarne Priory on Holy Island.

153 x 153 cms (60 x 60 inches)

Oil, gesso and graphite on aluminium and parchment mounted on 12mm marine plywood. Some 3D objects including several small boats of different sorts cast in plaster as well as found objects such as buttons, horsehair, reeds, coins and fishing tackle, wire and nylon.

She talks about it here, and includes some details:

‘The work had a variety of starting points, the original ‘brief’ being to make a piece of work about the unique landscape of the Holy Island of Lindisfarne, thinking about ‘Pilgrimage’, ‘Place’ and ‘Nature’. It is a response to Katrina Porteous’ radio poem ‘The Refuge Box’ which is a rich and complex narrative of voices from across the centuries, and including the words of an Eritrean refugee and recordings from HM Coastguard called out to rescue stranded motorists caught by the dangerous tide. I had produced an etching to illustrate her poem many years ago.

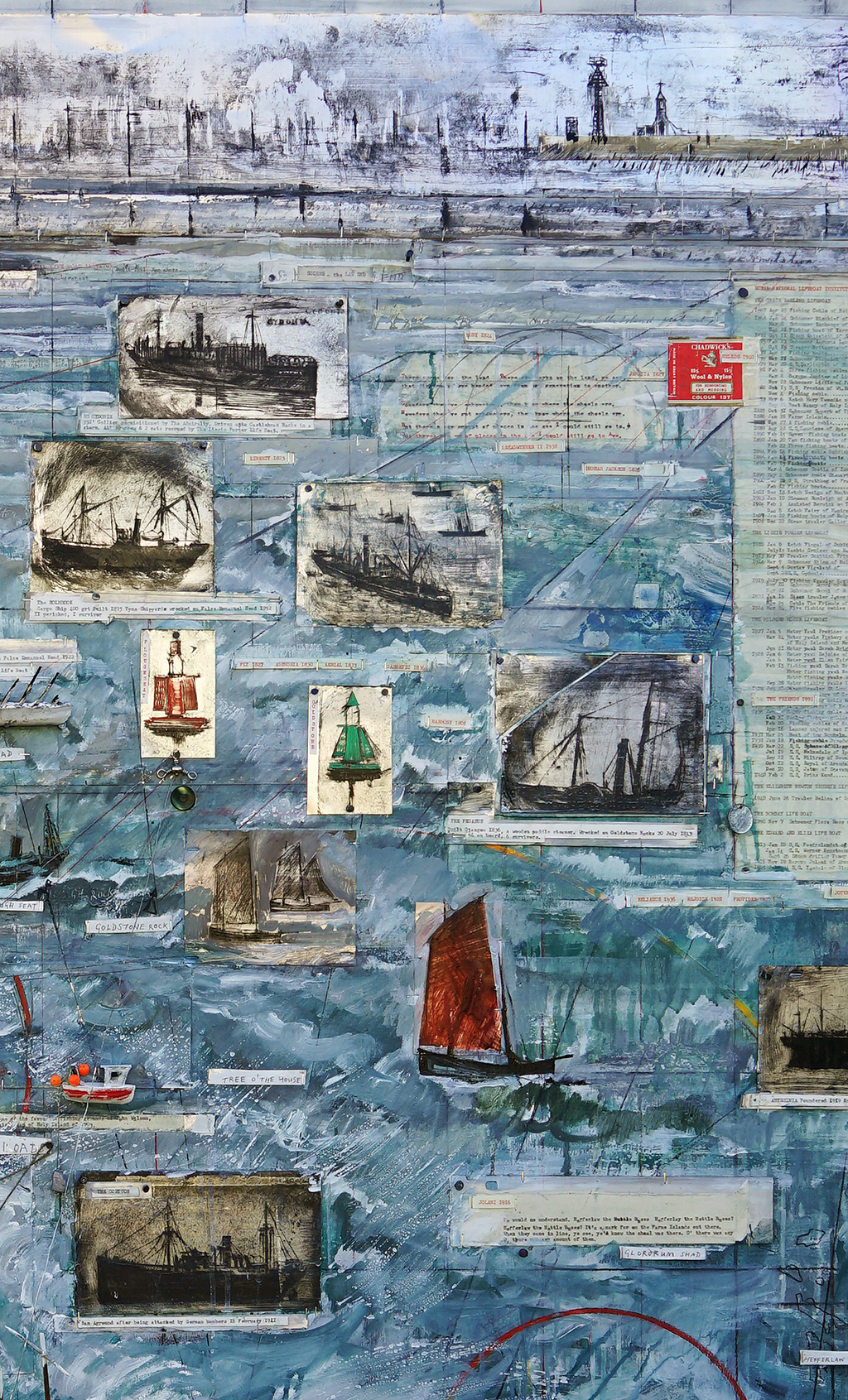

‘This poem forms the literal basis of the artwork, written out in full on parchment, then partially erased by layers of paint. The Lindisfarne Gospels were created on Lindisfarne, with calf skin prepared by the monks on the island. I have used a paper imitation parchment in place of calf skin. Parchment is also used to type and write out the entire list of rescues carried out by the Holy Island lifeboats of which there were many, since the waters around Lindisfarne are some of the most dangerous inland waters in the UK. I have represented some of the numerous wrecks with small drypoint plates, relating to the place of their sinking/grounding.

‘The lifeboats were manned entirely by the islanders, mostly fishermen, and often women were involved in the launching of the boats. Women were also involved in the baiting of the long lines, used in herring fishing which, until the early part of the C20th was a key part of the islands’ life and income. The buttons used for the lifeboat wheels are a reference to the women and the essential but often unseen role they played in the fishing industry, baiting lines, mending nets, and undoubtedly many other things beside. There is also a small string of buttons which I made to represent one of the victims of one of the many shipwrecks off Holy Island, Miss Sarah Briggs. Her sewing things were discovered washed up on the shore. The string of buttons is also an echo of the beautiful string of St Cuthbert beads or crinoid fossils, which is displayed nearby in the museum.

‘As well as Katrina’s poem, the work is made to an exact charting of the coastline, based on Sea Chart 111. Contrasting with this aerial perspective there is the ubiquitous ‘horizon’ of the Causeway which stretches along the top of the work, again using drypoint on aluminium to try to achieve the liminality of land, sea and sky. Here we see the three different refuge boxes, the posts of the pilgrims’ causeway and the different beacons on the island, including the Black Beacon, the steel of St Marys church, and Emmanuel Head.

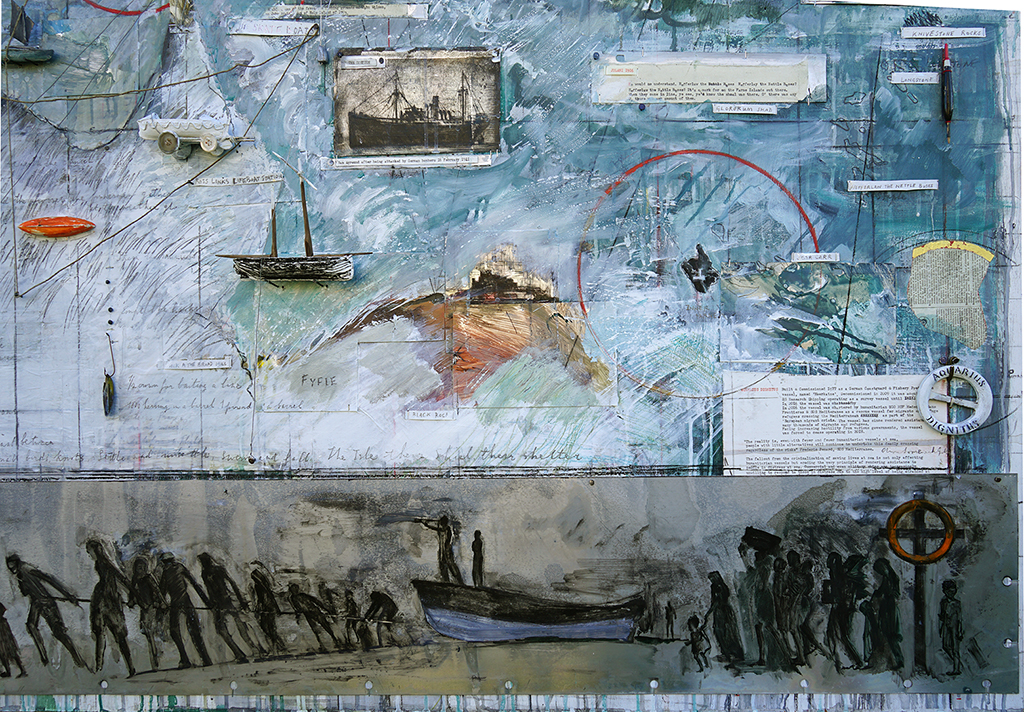

‘Along the bottom of the work there is another horizon with a procession of figures. There is a group of figures carrying a coffin, perhaps that of St Cuthbert whose relics were removed from the island when the Vikings arrived. Then there are the people involved in launching or bringing in the lifeboat, followed by a small family group of, who knows, people seeking refuge, which is what Holy Island has provided for so many over the centuries.

‘At the centre of the work, on the island itself, there is a roughly cast herring boat with a tree bedded in broken mussel shells. The tree is adorned with ropes and brightly coloured buoys and is inspired by a tree that is behind the harbour, and used as a playing ground. When I saw it for the first time it reminded me of a shrine, decorated with votive offerings, as we find in cultures all over the world. St Cuthbert is represented by a rusty ‘traveller’ (a metal ring used in long line fishing) partly gilded with gold leaf; this hangs over St Cuthbert’s Island.

‘It was extremely important to me that this work, which will hopefully hang in the island’s museum for many years, really spoke to and about the islands’ community, of which fishing has been at the heart over the centuries. I have included many of the ‘Fishermen Marks’, now a lost language used by fishermen in the pre-echo-meter era, by which to navigate. These relate stories and people to places, like a form of poetry, and likewise there are words and phrases of some of the islanders who I met and listened to, included in the work.

‘When I visited the museum and saw the work in place I was delighted to see it alongside some extraordinary artefacts from the Anglo Saxon and later periods of the island’s history, particularly the necklace of St Cuthbert’s beads (crinoid fossils), the necklace or rosary of salmon vertebrae, and the C17-18th wool crochet and rare bone button with four holes. Now, to see the work hanging amongst and alongside these treasures, and to see people passing through the exhibition and examining the displays in such detail, it makes me very proud to have been part of this project.’